In the journals: Yoga therapy helps relieve chronic lower back pain

In the journals

Yoga therapy helps relieve chronic lower back pain

Once regarded as an esoteric Eastern discipline, yoga is now a familiar part of the health and fitness scene in the United States. A national survey released in 2008 found that nearly 16 million Americans — more than 11 million of them women — currently practice yoga. Another nine million Americans say they plan to try yoga within the year. Although many people adopt the practice to ease stress and improve overall health, a growing number have specific medical aims and are following the recommendations of their clinicians.

According to a study in the journal Spine (Sept. 1, 2009), yoga therapy can reduce pain and functional impairment in people with chronic (lasting more than three months) low back pain. This condition is notoriously difficult to treat, and not surprisingly, one of the most commonly reported reasons for turning to alternative and complementary therapies. Yoga has shown promise in treating the condition, but not all studies have looked at the same form of yoga. The Spine study is the second of two randomized trials to test a form called Iyengar (pronounced eye-en-gar) yoga, which is based on the teachings of the eponymous nonagenarian B.K.S. Iyengar.

What is Iyengar yoga?

Most yoga taught and practiced in this country is hatha yoga, which combines three elements: classic poses (asanas), controlled breathing, and deep relaxation or meditation. Iyengar is a type of hatha yoga involving the use of props such as blankets, blocks, benches, and belts to help people perform the poses to the fullest extent possible even if they lack experience or have physical limitations. The emphasis is on precise physical alignment, with trained teachers adjusting everything from the position of the shoulders to the angle of the toes.

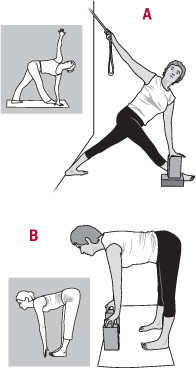

Iyengar adjustments to classic yoga poses

Iyengar yoga uses blocks, belts, and other props to help students perform classic yoga poses such as those shown in the grey insets above: parivrtta trikonasana, or the revolved triangle pose (A), and ardha uttanasana, or the standing half forward bend (B). Instructions are individualized, with adjustments made for age, experience, body type, physical condition, and medical problems. |

The study

With funding from the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, researchers at West Virginia University enrolled 90 adults (75% of them women) to participate in a yearlong trial comparing the effects of Iyengar yoga therapy with those of standard medical care. Participants ranged in age from 23 to 66, and all were suffering chronic low back pain. About half of them were assigned to 24 weeks of a twice-weekly, 90-minute regimen approved by B.K.S. Iyengar and taught by a certified Iyengar yoga instructor and two assistants with experience in teaching yoga therapy to people with chronic low back pain. On days when they didn't have a yoga class, they were instructed to practice at home for 30 minutes using a DVD, props, and an instruction manual. The rest of the participants (the control group) continued with usual medical care and were followed with monthly telephone calls to gather information about their medications or other therapies.

All subjects reported on functional disability, pain intensity, depression, and medication use at the start of the study, midway through (12 weeks), immediately afterward (24 weeks), and at a follow-up six months later. Compared with the control group, the Iyengar group experienced a 29% reduction in functional disability, a 42% reduction in pain, and a 46% reduction in depressive symptoms at 24 weeks. There was also a greater trend toward lower medication use in the yoga group. There were no reports of adverse effects.

Six months after the trial ended, 68% of the yoga group were still practicing yoga — on average, three days a week for at least 30 minutes. Their levels of functional disability, pain, and depression had increased slightly but were still lower than those of the control group.

The study had limitations — a small number of participants, as well as reliance on the participants' own reports of symptoms and disability. Also, the control group, on average, had been suffering back pain longer than the yoga group. Still, the results are consistent with findings from other studies of yoga for low back pain.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.