Big toe got you down? It may be hallux rigidus

A stiff and painful big toe can knock you off your feet. Here's what you can do about big toe joint pain caused by hallux rigidus.

- Reviewed by Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

The big toe may be small, but its role in our lives is enormous. Just imagine how hard it would be to walk, run, squat, bend over, rise up on the balls of the feet, or simply keep your balance without the aid of your big toes.

A crucial element of big-toe function is the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, which joins the first long bone (metatarsal) in the forefoot to the first bone of the big toe (proximal phalanx). Every time you take a step, the MTP joint bends, allowing the foot to roll forward and push off. During this phase of the walking cycle, the joint supports 50% of the body's weight. If the joint doesn't function properly, not only walking, but also exercising and many other activities of daily life can be difficult, sometimes impossible. One of the most common ailments of the big toe joint is hallux rigidus — literally, "stiff big toe."

Anatomy of hallux rigidus

In hallux rigidus, osteoarthritis breaks down the cartilage covering the ends of the bones that make up the big toe joint. Joint space narrows and bone spurs (osteophytes) may form. |

Hallux rigidus is the loss of flexibility in the big toe due to arthritis in the MTP joint. In an earlier stage of the condition, called hallux limitus, movement is only somewhat affected and conservative measures can often relieve pain and improve function. If pain and stiffness worsen, surgery is an option.

How does hallux rigidus develop?

In the MTP joint, like other joints in the body, the ends of the bones are covered with articular cartilage, a slick substance that aids in smooth joint movement. Age-related degeneration, genetic factors, or acute injury can cause articular cartilage to break down — a process known as osteoarthritis or degenerative arthritis. Often there also is inflammation, which leads to more pain and stiffness. Bone spurs (osteophytes) may develop on top of the bones, and the joint space may narrow, reducing the joint's motion. This can impinge on the way you walk and contribute to pain in the ball of the foot and even the back.

It's not entirely clear why hallux rigidus develops in some people and not in others. Hereditary or congenital defects in the foot or faulty foot mechanics can place chronic stress on the big toe joint, triggering arthritis. Certain athletic injuries have also been implicated. For example, "turf toe," so-named because it often happens to people who play games on artificial surfaces, is an injury to the MTP joint caused by the sudden bending back of the big toe. A toe stub or break can contribute to degeneration of the joint, as can an inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis and the metabolic disorder gout. Injury also occurs in certain dance disciplines (notably ballet) that require repetitive use of positions such as demi-pointe, which forces the MTP joint to flex at a 90° angle. Some research suggests that women are more likely to develop hallux rigidus, but studies are inconsistent.

What to do about hallux rigidus?

Early signs of hallux rigidus include pain and stiffness in the big toe joint during use, such as walking or exercising, especially as the foot rolls forward to push off. The joint may also become swollen and red. It's important to see a clinician early. If you wait until bone spurs develop or the toe is completely stiff or hurts all the time, restoring function can be more difficult. Also, you can develop other foot and joint problems if you start walking on the outer edge of the foot to avoid putting pressure on the toe.

Your clinician will examine the toe and may order x-rays to check for bone spurs, cartilage degeneration, loss of space between the bones of the joint, and other possible toe problems. Treatment usually starts with conservative measures aimed at the following goals:

- Symptom relief. Rest, ice, and topical lidocaine or topical anti-inflammatory medications can help relieve pain. For severe pain, your clinician may recommend treating the joint with a corticosteroid injection, sometimes in combination with an anesthetic.

- Improved foot mechanics. For longer-lasting relief, it's important to correct some of the things that may be aggravating the big toe. High heels are out, and shoes with a spacious toe box are in. Your clinician may recommend a thick-soled shoe or one with a rocker bottom (like a clog), which allows the foot to roll forward as you walk, so that your big toe doesn't bend sharply. Shoe inserts (orthoses) may help correct abnormalities of the foot or problems with the way you walk that could be contributing to the problem. A shoe stretcher can be used to loosen the toe box and other areas of the shoe that come in contact with the big toe or big toe joint.

- Injury prevention. Try to avoid physical activity that places high-impact stress on the foot, such as running, jumping, and activities that involve bursts of activity and quick stops, like tennis. Swimming and bicycling are good alternatives. If the big toe isn't completely stiff, you may be able to improve its upward flexibility with some simple range-of-motion exercises. For example, grasp your big toe and gently pull it back until the point of resistance. Hold the position for 20 seconds. Repeat several times a day. A regular schedule of walking can also help.

What about surgery for hallux rigidus?

Surgery should be considered only if conservative treatment doesn't help your big toe joint pain and pain and stiffness are preventing you from wearing shoes or are limiting your normal activities. The choice of operation depends on several factors, including the extent of the osteoarthritis, the severity of pain and disability, and an individual's level of activity. Two of the recommend procedures are cheilectomy (kye-LEK-tuh-me) and joint fusion (arthrodesis).

During cheilectomy, the surgeon removes bone spurs and other bony material from the MTP joint through an incision along the top of the joint. Sometimes a cut (osteotomy) is made in the big toe bone to improve the toe's upward movement. A special shoe must be worn for two weeks after surgery, and swelling may last for several months. If osteotomy is involved, recovery takes longer, and weight must be kept off the foot during healing. Exercises and sometimes physical therapy are usually recommended to improve range of motion. Studies of people with mild to moderate osteoarthritis who undergo cheilectomy suggest that most of them experience big toe joint pain relief and improved joint function. Sometimes arthritis worsens, and additional surgery is recommended down the road.

Surgery for hallux rigidus: Cheilectomy

During cheilectomy, bony material is cut away from around the joint, allowing it to bend upward more freely. |

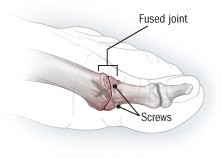

If pain and stiffness are more severe, especially in very active people, joint fusion (arthrodesis) is usually recommended. The articular surfaces of the joint are removed, and the two bones are brought together and fixed in place. Several devices can be used to hold the bones together, including wires, pins, screws, and plates. The bones take about three months to fuse; during that time, crutches are used to keep weight off the foot. Since the resulting joint doesn't bend, the toe is turned slightly upward, to allow for walking, and shoes with rocker-type soles are usually needed. But the procedure eliminates most big toe joint pain, and people can often return to athletic activities.

Surgery for hallux rigidus: Joint fusion

When pain and stiffness are severe, especially in very active people, surgeons often recommend joint fusion. In this procedure, the bones of the big toe joint are trimmed and joined with screws or another device. |

For moderate to severe hallux rigidus in older, less active people, surgeons often recommend arthroplasty, which removes bone from the big toe and aligns the bones of the joint with a pin (which is removed after healing). The bones don't fuse but are connected by scar tissue, which eliminates bone-on-bone problems. However, the toe loses some of its push-off power and weight-bearing ability. Transferring the weight to the smaller toes may result in pain in those joints. Artificial joint replacement is another option, but there's little data on long-term outcomes, and studies are needed to compare the procedure to fusion.

About the Reviewer

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.