What to do about rotator cuff tendonitis

The best way to treat rotator cuff tendonitis, one of the most common causes of shoulder pain, is with simple home therapies.

- Reviewed by Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Swinging a tennis racket, digging in the garden, placing a book on a high shelf, and reaching back to insert your arm into a sleeve — these are some of the movements made possible by the shoulder's enormous range of motion. We use this mobility in so many activities that when the shoulder hurts, it can be disabling. For younger people, sports injuries are the main source of trouble, but the rest of us have more to fear from the normal wear and tear that, over time, weakens shoulder tissues and leaves them vulnerable to injury. The risk is greatest for people with occupations or hobbies that require repetitive or overhead movements, such as carpenters, painting, tennis, or baseball.

One of the most common causes of shoulder pain is rotator cuff tendonitis — inflammation of key tendons in the shoulder. The earliest symptom is a dull ache around the outside tip of the shoulder that gets worse when you push, pull, reach overhead, or lift your arm up to the side. Lying on the affected shoulder also hurts, and the pain may wake you at night, especially if you roll onto that shoulder. Even getting dressed can be a trial. Eventually, the pain may become more severe and extend over the entire shoulder.

When severe, tendonitis can lead to the fraying or tearing of tendon tissue. Fortunately, rotator cuff tendonitis and even tears can usually be treated without surgery.

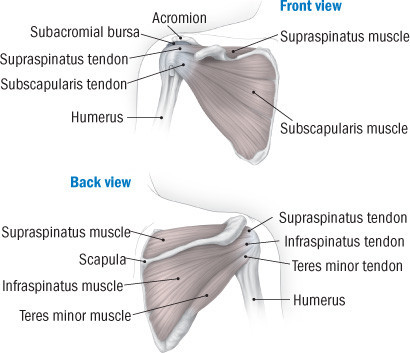

Anatomy of the rotator cuff

The rotator cuff comprises four tendons — the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis; each of them attaches a muscle of the same name to the scapula (shoulder blade) and the humerus, or upper arm bone (see illustration). The tendons work together to stabilize the joint, rotate the shoulder, and lift the arm above the head. Rotator cuff tendonitis usually starts with inflammation of the supraspinatus tendon and may involve the three other tendons as the condition progresses.

Rotator cuff

|

Rotator cuff diagnosis

Most clinicians diagnose rotator cuff tendonitis by taking a history and performing a physical examination. However, if you've suffered a traumatic injury or the shoulder hasn't improved with conservative therapy, or if a tear is suspected, an x-ray or MRI may be ordered. Your clinician will also check for tenderness at a point near the top of the upper arm (the subacromial space) and look for pain as the arm is raised and moved in certain ways. Your muscle strength and the shoulder's range of motion will also be tested. Pain with normal muscle strength suggests rotator cuff tendonitis; pain with weakness may indicate a tear (see "What about a rotator cuff tear?"). Because it's difficult to assess strength when the shoulder hurts, your clinician may recommend an injection of a numbing agent (lidocaine) to deaden the pain before making an evaluation.

What about a rotator cuff tear?As we get older, tendon tissue thins out and a tear becomes more likely. Up to one-third of older people with rotator cuff tendonitis have a tear. Minor ones can be treated conservatively, like tendonitis, but major ones may require an operation. Those caused by traumatic injury to the shoulder are often repaired surgically. However, recovery tends to be slow. Many orthopedic surgeons prefer to reserve surgery for younger patients, major tears that are diagnosed early, and older people whose occupations or activities place heavy demands on their shoulders.

The operation can be performed arthroscopically — a minimally invasive procedure in which surgical instruments are inserted through several tiny incisions — or through standard open surgery, which requires a larger incision. Some surgeons use a technique called "mini-open repair," which is somewhat less invasive and uses a smaller incision. All three procedures have similar long-term results, although less invasive procedures usually result in shorter hospital stays and less postsurgical pain. However, not all types of tears can be treated arthroscopically. |

Rotator cuff treatment

The minimum time for recovery from rotator cuff tendonitis or a small tear is generally two to four weeks, and stubborn cases can take several months. Early on, the aim is to reduce swelling and inflammation of the tendons and relieve compression in the subacromial space. Later, exercises can be started to strengthen the muscles and improve range of motion.

During the first few days of rotator cuff tendonitis, apply an ice pack to the shoulder for 15 to 20 minutes every four to six hours. If you still have a lot of rotator cuff pain, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as ibuprofen, may be helpful. Your clinician may also suggest a corticosteroid injection, but there's no clear evidence that this offers any advantage in the long term over physical therapy and NSAID use.

While you're in pain from rotator cuff tendonitis, avoid lifting or reaching out, up, or overhead as much as possible. On the other hand, you don't want to stop moving your shoulder altogether, because that can lead to "frozen shoulder," a condition in which the tissues around the shoulder shrink and reduce its range of motion.

Rotator cuff stretches

The weighted pendulum exercise (see below) is recommended to reduce pressure on the rotator cuff by widening the space the tendons pass through. As your rotator cuff tendonitis improves, physical therapy with stretching and muscle-strengthening exercises becomes important. A physical therapist can help you with these exercises, but most of them you can also do on your own. Before exercising, warm up your muscles and tendons in a warm shower or with a heating pad. You may experience some mild soreness with muscle-toning exercises — ice applied to the shoulder should help relieve it — but if you develop sharp or severe pain, stop the exercises for a few days.

Weighted pendulum exercise

Sit or stand holding a 5- to 10-pound weight in the hand of the affected shoulder. Use a hand weight or make one from a gallon container filled with water. Relax the shoulder and allow the arm to hang straight down. Lean forward at a 20- to 25-degree angle (if you're standing, bend your knees slightly for a base of support), and swing your arm gently in a small circle, about one foot in diameter. Perform 10 circles in each direction, once or twice a day. As symptoms improve, you can make the circle wider — but never force it. |

Stretching exercisesWarm your muscles before performing these exercises. |

|

Towel stretch. Grasp a dishtowel behind your back and hold it at a 45-degree angle. Use your good arm to gently pull the affected arm up toward the lower back. Do this stretch 10 to 20 times per day. You can also perform this exercise while holding the towel horizontally. |

|

Cross-body stretch. Sitting or standing, use the unaffected arm to lift the affected arm at the elbow and bring it up and across your body. Press gently, just above the elbow, to stretch the shoulder. Hold the stretch for 15 to 20 seconds. Do this exercise 10 to 20 times per day. |

|

Finger walk. Stand facing a wall at a distance of about three-quarters of an arm's length away. With the affected arm, reach out and touch the wall at about waist level. Slowly walk your fingers up the wall, spider-like, as far as you comfortably can or until you raise your arm to shoulder level. Your fingers should be doing most of the work, not your shoulder muscles. Keep the elbow slightly bent. Slowly lower the arm — with the help of your good arm, if necessary. Perform this exercise 10 to 20 times a day. You can also try this exercise with the affected side facing the wall. |

Isometric muscle toning exercisesHeat and stretch your shoulder joint before doing these exercises. Use flexible rubber tubing, a bungee cord, or a large rubber band to provide resistance. |

|

Inward rotation. Hook or tie one end of the cord or band to the doorknob of a closed door. Holding your elbow close to your side and bent at a 90-degree angle, grasp the band (it should be neither slack nor taut) and pull it in toward your waist, like a swinging door. Hold for five seconds. |

|

Outward rotation. Hold your elbows close to your sides at a 90-degree angle. Grasp the band in both hands and move your forearms apart two to three inches. Hold for five seconds. Do 15 to 20 sets of these exercises each day. |

Image: Jan-Otto/Getty Images

About the Reviewer

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.