Exercise and aging: Can you walk away from Father Time

The clock ticks for all men, and with each tick comes change. For men who manage to avoid major medical problems, the changes are slow and gradual, but they do add up. Here are some things that aging can do to you — if you give up and let Father Time take his toll.

Some of the changes of aging start as early as the third decade of life. After age 25–30, for example, the average man's maximum attainable heart rate declines by about one beat per minute, per year, and his heart's peak capacity to pump blood drifts down by 5%–10% per decade. That's why a healthy 25-year-old heart can pump 2½ quarts of blood a minute, but a 65-year-old heart can't get above 1½ quarts, and an 80-year-old heart can pump only about a quart, even if it's disease-free. In everyday terms, this diminished aerobic capacity can produce fatigue and breathlessness with modest daily activities.

Starting in middle age, a man's blood vessels begin to stiffen and his blood pressure often creeps up as well. His blood itself changes, becoming more viscous (thicker and stickier) and harder to pump through the body, even though the number of oxygen-carrying red blood cells declines.

Most Americans begin to gain weight in midlife, putting on 3–4 pounds a year. But since men start to lose muscle in their 40s, that extra weight is all fat. This extra fat contributes to a rise in LDL ("bad") cholesterol and a fall in HDL ("good") cholesterol. It also helps explain why blood sugar levels rise by about 6 points per decade, making type 2 diabetes distressingly common in senior citizens.

The loss of muscle continues, eventually reducing a man's musculature by up to 50%, which contributes to weakness and disability. At the same time, muscles and ligaments get stiff and tight. Although men have a lower risk of osteoporosis ("thin bones") than women, they do lose bone calcium as they age, increasing the risk of fractures. One reason for the drop in muscle mass and bone density is a drop in the male hormone testosterone, which declines by about 1% per year after the age of 40. Though most men continue to have normal testosterone levels and reproductive capacity throughout life, many experience a gradual decline in libido and sexual vigor.

The nervous system also changes over time. Reflexes are slower, coordination suffers, and memory lapses often crop up at embarrassing times. The average person gets less sleep in maturity than in youth, even if he no longer needs to set his alarm clock. Not surprisingly, spirits often sag as the body slows down.

It sounds grim — and these changes happen to healthy men. Men with medical problems start to age earlier and slow down even more. All in all, aging is not for sissies.

No man can stop the clock, but every man can slow its tick. Research shows that many of the changes attributed to aging are actually caused in large part by disuse. It's new information, but it confirms the wisdom of Dr. William Buchan, the 18th-century Scottish physician who wrote, "Of all the causes which conspire to render the life of a man short and miserable, none have greater influence than the want of proper exercise." And about the same time, the British poet John Gay agreed: "Exercise thy lasting youth defends."

Exercise is not the fountain of youth, but it is a good long drink of vitality, especially as part of a comprehensive program (see box below). And a unique study from Texas shows just how important exercise can be.

The Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study

In 1966, five healthy men volunteered for a research study at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. It must have sounded like the opportunity of a lifetime; all they had to do was spend three weeks of their summer vacation resting in bed. But when they got out of bed at the end of the trial, it probably didn't seem so good. Testing the men before and after exercise, the researchers found devastating changes that included faster resting heart rates, higher systolic blood pressures, a drop in the heart's maximum pumping capacity, a rise in body fat, and a fall in muscle strength.

In just three weeks, these 20-year-olds developed many physiologic characteristics of men twice their age. Fortunately, the scientists didn't stop there. Instead, they put the men on an 8-week exercise program. Exercise did more than reverse the deterioration brought on by bed rest, since some measurements were better than ever after the training.

The Dallas study was a dramatic demonstration of the harmful consequences of bed rest. It's a lesson that's been learned yet again in the era of space travel, and it has helped change medical practice by encouraging an early return to physical activity after illness or surgery. And by revisiting the question 30 years later, the Texas researchers have also been able to investigate the interaction between exercise and aging.

A second look

The original subjects all agreed to be evaluated again at the age of 50. All five remained healthy, and none required long-term medication. Even so, the 30-year interval had not been kind. Over the years, the men gained an average of 50 pounds, or 25% of their weight at age 20. Their average body fat doubled from 14% to 28% of body weight. In addition, their cardiac function suffered, with a rise in resting heart rate and blood pressure and a fall in maximum pumping capacity. In terms of cardiac function, though, the toll of time was not as severe as the toll of inactivity; at 50, the men were far below their 20-year-old best, but they were not quite as feeble as when they emerged from three weeks of bed rest in 1966.

The researchers did not ask the 50-year-old volunteers to lie in bed for three weeks; that could have been hazardous. But they did ask them to begin an exercise program, and they wisely constructed a gradual 6-month regimen of walking, jogging, and cycling instead of the 8-week crash course that served the 20-year-olds so well.

Slow but steady endurance training carried the day. At the end of the six months, the men averaged only a modest 10-pound loss of their excess weight, but their resting heart rates, blood pressures, and their heart's maximum pumping abilities were back to their baseline level from age 20. All in all, exercise training reversed 100% of the 30-year age-related decline in aerobic power. Even so, exercise did not take the men back to their peak performance after 8 weeks of intense training at age 20. The clock does tick, after all, but exercise did slow the march of time.

The Dallas scientists contributed a great deal to our understanding of exercise and aging, but they did not seize the opportunity to evaluate many of the changes that men experience as they age. Fortunately, other research has filled in the gaps. To avoid gaps as you age, construct a balanced exercise program.

Endurance training. As the Texas studies showed, endurance exercise is the best way to improve cardiovascular function. It helps keep the heart muscle supple and the arteries flexible, lowers the resting heart rate, and boosts the heart's peak ability to deliver oxygen-rich blood to the body's tissues. A related benefit is a fall in blood pressure.

Endurance exercise is also the best way to protect the body's metabolism from the effects of age. It reduces body fat, sensitizes the body's tissues to insulin, and lowers blood sugar levels. Exercise boosts the HDL ("good") cholesterol and lowers levels of LDL ("bad") cholesterol and triglycerides. And the same types of activity will fight some of the neurological and psychologic-al changes of aging. Endurance exercise boosts mood and improves sleep, countering anxiety and depression. In addition, it improves reflex time and helps stave off age-related memory loss. All in all, many of the changes that physiologists attribute to aging are actually caused by disuse. Using your body will keep it young (see table below).

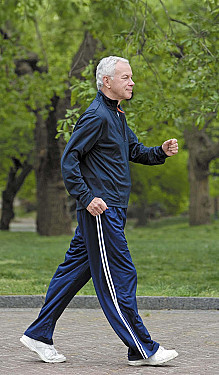

The Dallas investigators prescribed walking, jogging, and biking for endurance training. They could have achieved the same benefits with swimming, racquet sports, rowing, cross-country skiing, aerobic dance, and even golf (as long as players walk the course). A variety of exercise machines can also do the job, but only if you use them properly. The key is regular activity. Start slowly if you are out of shape, then build up gradually to 3–4 hours a week. A program as simple as 30 minutes of brisk walking nearly every day will produce major benefits.

|

Exercise vs. aging |

||

|

|

Effect of aging |

Effect of exercise |

|

Heart and circulation |

||

|

Resting heart rate |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Maximum heart rate |

Decrease |

Slows the decrease |

|

Maximum pumping capacity |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Heart muscle stiffness |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Blood vessel stiffness |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Blood pressure |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Blood |

||

|

Number of red blood cells |

Decrease |

No change |

|

Blood viscosity ("thickness") |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Lungs |

||

|

Maximum oxygen uptake |

Decrease |

No change |

|

Intestines |

||

|

Speed of emptying |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Bones |

||

|

Calcium content and strength |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Muscles |

||

|

Muscle mass and strength |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Metabolism |

||

|

Metabolic rate |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Body fat |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Blood sugar |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Insulin levels |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

LDL ("bad") cholesterol |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

HDL ("good") cholesterol |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Sex hormone levels |

Decrease |

Slight decrease |

|

Nervous system |

||

|

Nerve conduction and reflexes |

Slower |

Decrease |

|

Quality of sleep |

Decrease |

Increase |

|

Risk of depression |

Increase |

Decrease |

|

Memory lapses |

Increase |

Decrease |

Resistance exercise using light weights or exercise machines will enhance muscle mass and strength and preserve bone calcium. You'll need to learn what to do, and instructors can help. But with simple directions and precautions, most men can develop a safe and effective home program for themselves.

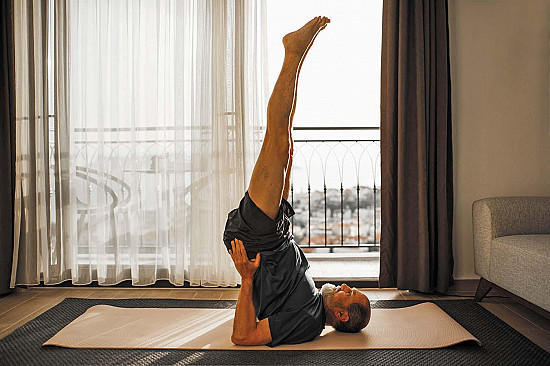

Flexibility training will help keep you supple as you age. Stretching exercises are an ideal way to warm up before and cool down after endurance exercise. Like strength training, 20 minutes of dedicated time two or three times a week is ideal. Yoga classes are very helpful, but most men can learn to stretch for health on their own.

Exercises for balance will also help retard some common effects of aging. They will help you move gracefully, avoid injuries, and prevent the falls that cripple so many older Americans.

Helen Hayes was right when she proclaimed, "Resting is rusting." But although exercise can do much to remove the rust of aging, it can't do it all. Even a balanced exercise program won't keep reading glasses off a man's nose or prevent cataracts from forming in due time. Exercise can't keep a man's prostate small or his testosterone levels high, but it can reduce his risk of erectile dysfunction.

To keep your body as young as possible for as long as possible, keep it moving. As usual, Hippocrates got it right about 2,400 years ago, explaining, "That which is used develops; that which is not wastes away."

Exercise, illness, and longevity

A proper exercise program will help men delay many of the changes of aging, particularly when they combine it with other preventive measures (see "Not by exercise alone," below). And the same program can help ward off many of the chronic illnesses that too often tarnish a man's golden years.

Heart disease is the leading killer of American men. Because exercise helps improve so many cardiac risk factors (cholesterol, blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, and stress), it should have a powerful protective influence on heart attacks — and it does. Back in 1978, the Harvard Alumni Study found that men who exercise regularly are 39% less likely to suffer heart attacks than their sedentary peers. It was a groundbreaking observation, and it's been confirmed many times over.

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in America. Like heart disease, many strokes are caused by atherosclerosis, which is why heart attacks and stroke share so many risk factors. It's no surprise, then, that exercise can reduce the risk of stroke. Twenty-four years after its report on exercise and heart disease, the Harvard Alumni Study linked mild exercise to a 24% risk reduction; moderate to intensive exercise was even better, reducing risk by 46%.

Cancer is different — but exercise can also help fight the nation's second leading killer. Colon cancer is the clearest example; Harvard's Health Professionals Follow-Up Study found that highly active men are 47% less likely to develop the disease than their sedentary peers, and many other studies agree. Although the evidence is far less conclusive, regular exercise may even help prevent prostate cancer.

|

Exercise precautions Exercise is wonderful for health — but to get gain without pain, you must do it wisely, using restraint and judgment every step of the way. Here are a few tips:

|

Helping to prevent heart disease, cancer, stroke — exercise is worth the effort. And there's more. Physical activity can help reduce your risk for many of the chronic illnesses that produce so much distress and disability as men age. The list includes hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, and even Alzheimer's disease. It also includes "minor" ailments such as painful gallbladder attacks and bothersome symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. And if that's not enough motivation, consider that the Health Professionals Study linked regular exercise to a 30% reduction in a man's risk of impotence.

Regular exercise helps people age more slowly and live healthier, more vigorous lives. And it also helps people live longer. Calculations based on the Harvard Alumni Study suggest that men who exercise regularly can gain about two hours of life expectancy for each hour of exercise. Over the course of a lifetime, that adds up to about two extra years. Maximum benefit does require regular exercise over the years, but it doesn't mean a trip to the gym every day. In fact, just 30 minutes of brisk walking every day will go a long way toward enhancing your health.

Calculations are one thing, observations another. Scientists have evaluated men in Hawaii, Seventh-day Adventists in California, male and female residents of Framingham, Massachusetts, elderly American women, British joggers, middle-aged Englishmen, retired Dutchmen, and residents of Copenhagen, among others. Although the details vary, the essential message is remarkably uniform: Regular exercise prolongs life and reduces the burden of disease and disability in old age. In reviewing the data, Dr. J. Michael McGinnis of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) concludes that regular physical activity appears to reduce the overall mortality rate by more than a quarter and to increase the life expectancy by more than two years compared with the sedentary population's average.

|

Do the stronger live longer? Insurance agents are not alone; doctors would also like to predict disability and longevity. Scientists working with the Honolulu Heart Program and the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study proposed a simple way to do just that. Between 1965 and 1970, they evaluated about 8,000 healthy men with an average age of 54. Each volunteer was tested for his maximal handgrip strength along with conventional risk factors. The scientists tracked the men for an average of 25 years. During that time, 37% of the men died; the survivors were 71–93 years of age. Grip strength in midlife did not predict longevity, but it did correlate with disability. The men who were strongest in middle age had the lowest risk of disabilities and dependency in old age, even after chronic illnesses were taken into account. Cardiovascular fitness and aerobic capacity do predict longevity. In the Hawaiian study, muscular strength did not, but it did predict infirmity in old age. |

It's never too late

One of the most impressive things about the Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study was that the men responded nearly as well to exercise training at 50 as they did at 20. In fact, men can benefit from exercise at any age, though senior citizens do need to take extra care, especially if they are just getting started. Perhaps the most dramatic example comes from a Harvard study that demonstrated important improvements in 87- to 90-year-old nursing home patients who were put on a weight-lifting program. This study evaluated muscular function, but the Harvard Alumni Study examined mortality. The latter study found that previously sedentary men who began exercising after the age of 45 enjoyed a 24% lower death rate than their classmates who remained inactive. The maximum benefits were linked to an amount of exercise equivalent to walking for about 45 minutes a day at about 17 minutes per mile. On average, sedentary people gained about 1.6 years of life expectancy from becoming active later in life.

Studies from Harvard, Norway, and England all confirm the benefits of exercise later in life. It's important research, but it confirms the wisdom of the Roman poet Cicero, who said, "No one is so old that he does not think he could live another year."

|

Not by exercise alone Exercise is one way to slow the aging process, but it works best in combination with other measures. Here are some other tips to help you age well:

|

Beat the clock

Aging is inevitable, but it has an undeservedly fearsome reputation. No man can stop the clock, but most can slow its tick and enjoy life as they age with grace and vigor. Jonathan Swift was right when he said, "Every man desires to live long, but no man would be old." Regular exercise, along with a good diet, good medical care, good genes, and a bit of luck, can make it happen.

Exercise and longevity — it's Darwin redux: The survival of the fittest.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.