Is alcohol good for your heart?

New research suggests it may raise cardiovascular disease risk.

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

A glass or two of wine with dinner. A few refreshing beers on a hot weekend. It's all part of a heart-healthy diet, right? After all, moderate alcohol intake is seen as a toast to your long-term cardiovascular health. Well, maybe not.

Over the years, studies have produced conflicting results. Some indicate alcohol protects against cardiovascular disease, including heart attack, heart failure, and stroke. Others imply the opposite. So, what's the real story? It now appears that alcohol is not the healthy elixir once thought. Growing evidence suggests that not only won't alcohol lower your risk for cardiovascular disease, but consuming moderate amounts may even increase it.

A study in studies

The problem with most alcohol-related research is that it consists almost entirely of observational studies that show associations, not cause and effect.

"No previous research has firmly established that drinking alcohol directly benefits heart health, such as by lowering high cholesterol levels or high blood pressure," says Dr. Krishna Aragam, a cardiologist with Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital. "Instead, most research has found that, in general, people who drink moderate amounts of alcohol often have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease."

But therein lies the rub. Is it the alcohol that offers protection, or something else? New research may have the answer.

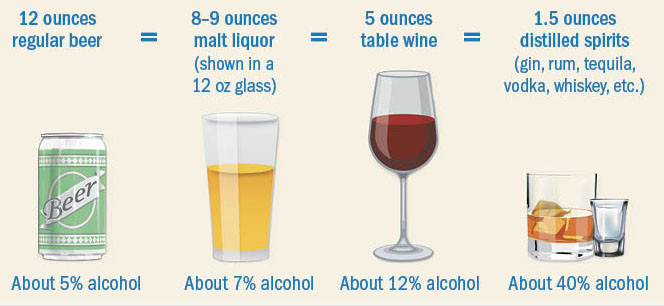

A study, published online March 25, 2022, by JAMA Network Open, found the general lifestyle habits of moderate drinkers — and not the drinking itself — were responsible for the group's lower risk for cardiovascular disease. Researchers looked at 371,463 adults who consumed an average of nine standard alcoholic drinks per week (see image). Weekly intake of one to eight drinks was deemed light; 8.5 to 15 drinks, moderate; and 15.5 to 24.5, heavy.

Consistent with earlier studies, the light and moderate drinkers had the lowest heart disease risk (even better than people who abstained from drinking). Yet, the researchers did not find evidence that alcohol specifically helped to lower blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, or C-reactive protein levels — all common markers for cardiovascular disease risk. This implied that something else was responsible.

What's a standard drink?

All of the above drinks contain about the same amount of alcohol, despite their different sizes. Each counts as a single or standard drink. Depending on the recipe, a mixed drink may contain one, two, or more standard drinks, as shown in a cocktail content calculator from the National Institutes of Health (see /cocktail). Source: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH. |

Less is more

Looking closer, the research team found that as a group, light to moderate drinkers had healthier habits than abstainers. In general, they were more physically active, ate more vegetables and less red meat, and didn't smoke. And their body mass index was lower overall.

"Taking just a few of these lifestyle factors into account significantly lessened any potential benefits associated with alcohol consumption," says Dr. Aragam. "This suggests that healthy habits, and not alcohol consumption, may be what offered protection from cardiovascular disease."

But that was not all. The study also revealed large differences in cardiovascular risk across the spectrum of alcohol consumption. When the researchers set aside the impact of lifestyle habits and looked only at the link between alcohol intake and cardiovascular risk, they found a minimal increase in risk among light drinkers. However, the risk steadily climbed once the weekly amounts reached seven drinks. "The more people drank per week, the greater the risk," says Dr. Aragam.

Glass half full

Does this mean you can never enjoy an adult beverage? "For most people, there is no problem with the occasional alcoholic drink or two," says Dr. Aragam. He points out that most people don't drink every day or on a consistent weekly basis, so even self-described moderate drinkers probably drink much less than the individuals in studies.

"Still, you should probably weigh your alcohol intake with your overall heart health," says Dr. Aragam. It's best to speak with your doctor about what the proper amount of alcohol should be for you.

Image: © ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

About the Author

Matthew Solan, Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.