Kidney health quick-start guide

Your kidneys deserve as much care and protection as your heart or brain. Here's why, and what you can do.

- Reviewed by Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Health Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

We all want to protect our heart and our brain. But how often do you think about protecting your kidneys? The health of those two bean-shaped organs is easy to take for granted, especially since there aren't noticeable signs of trouble until chronic kidney disease — an irreversible loss of kidney function — has already developed. And with 37 million people in the United States struggling with the condition, and millions more at risk for developing it, it's important to pay attention to your kidneys now, when you can protect them.

The role of the kidneys

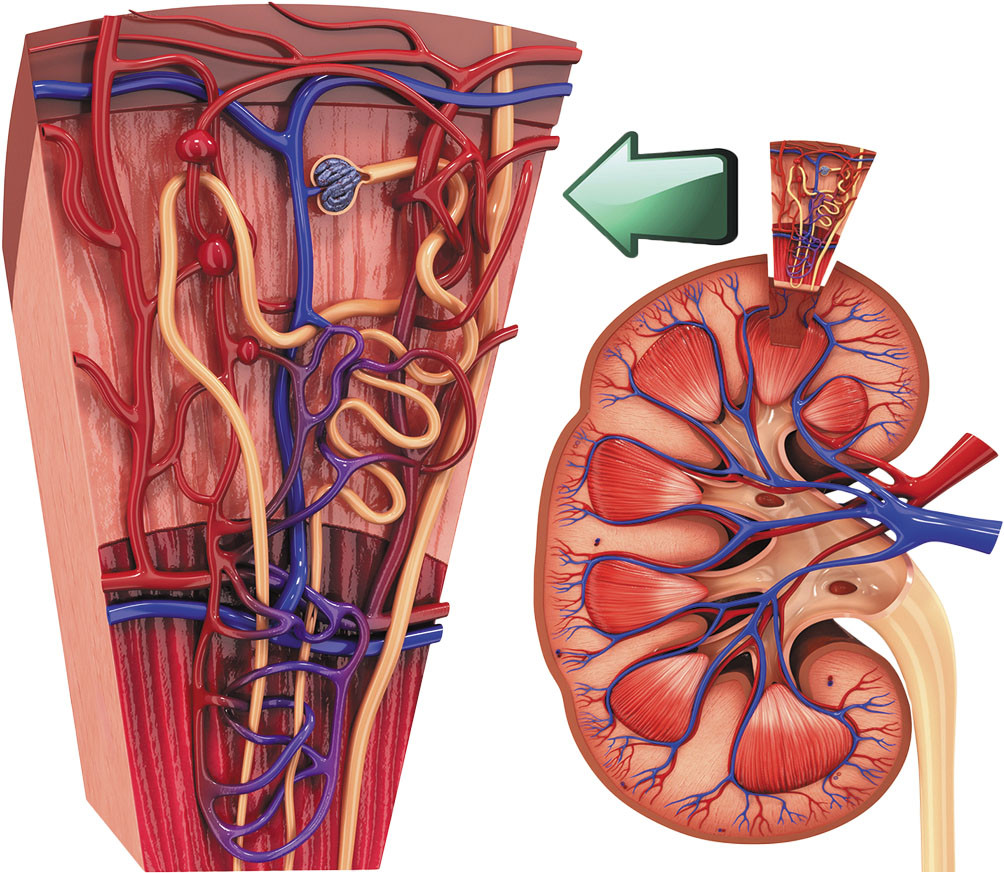

The kidneys — located on either side of the spine, just below your rib cage — perform many important functions. They route blood through a complex filtering system that removes toxins; hold on to fluid, salt, or other minerals the body needs; and send the waste (urine) to the bladder to be flushed out of the body.

These remarkable organs also help regulate your blood pressure, convert vitamin D to its active form, and release hormones needed for blood pressure control and red blood cell production.

Chronic kidney disease

Unhealthy lifestyle habits, chronic diseases, and genetic conditions can damage the kidneys and reduce their ability to do their many jobs.

"When your kidneys don't effectively flush out toxins, the toxins build up in the blood. That can hurt the heart and brain and cause problems with blood pressure, blood, bones, and nerves," says Dr. Joseph Bonventre, chief of the Division of Renal Medicine at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Samuel A. Levine Distinguished Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Treatment

If kidney disease is caught early, certain medications may slow its development. "For many years, we had only one set of drugs to protect against kidney disease progression. Those drugs target blood pressure and cardiovascular function. More recently, new drugs originally designed to treat diabetes, called SGLT2 inhibitors, have been found to help prevent kidney damage, even in people without diabetes," Dr. Bonventre says.

People with very advanced kidney disease need to have a machine filter their blood for them (a treatment called dialysis) or get a kidney transplant, breakthroughs pioneered at Harvard Medical School.

Protect your kidneys now

There's a lot you can do now to keep your kidneys healthy.

Control diabetes. Diabetes is the top cause of chronic kidney disease, likely because exposure to high blood sugar damages tiny blood vessels in the kidney. "The best things you can do if you have diabetes are to control blood sugar levels and lose weight," Dr. Bonventre says.

Reduce high blood pressure. High blood pressure is a major contributor to kidney disease progression. "High blood pressure can damage the kidney's filters and small blood vessels," Dr. Bonventre says.

Limit salt. Salt can cause your body to retain excessive fluids and raise blood pressure (in some people). The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend limiting salt intake to less than 2,300 milligrams per day. "Avoid salty restaurant and processed foods. Look for low-salt foods at the grocery store. And don't add salt to your food. Use other spices instead. And as long as your kidney function is good, you can use a salt substitute," Dr. Bonventre says.

Limit oxalate-rich foods. Spinach, almonds, cashews, and rhubarb are all loaded with oxalate, a chemical that can form kidney stones and deposits that sometimes lead to kidney disease. "You don't have to avoid these foods, but eat them in moderation. Don't eat a big plate of spinach every night," Dr. Bonventre says.

Watch your protein intake. Having too much protein in the diet forces the kidneys to work overtime. Can it harm them? "Some observational studies suggest that long-term high-protein diets can cause kidney disease. But it's hotly debated," Dr. Bonventre says. "Why take a chance? Limit protein to the recommended daily amount in grams, which is determined by multiplying your weight in pounds by 0.36."

Limit alcohol intake. Don't have more than one drink per day. Regular excessive alcohol drinking increases the risk for high blood pressure, contributes to weight gain, and makes the kidneys work harder. Over all, it may double the risk for kidney disease.

Lose weight if you need to. "Obesity makes the kidneys work harder than they need to do. This can ultimately cause the kidney filters to break down," Dr. Bonventre says.

Stop smoking. Smoking damages blood vessels, including those providing oxygen and nutrients to the kidneys. Smoking can also make drugs that treat high blood pressure less effective.

Exercise regularly. Aerobic exercise — the kind that makes your heart and lungs work hard, like brisk walking — helps blood vessels stay healthy, flexible, and able to expand and contract well. Aim for 150 minutes of aerobic exercise per week.

Stay hydrated. Getting enough fluids each day — from water or watery foods like fruit and soup — helps the kidneys flush out toxins from the body. You need about four to six cups of fluids per day to stay hydrated.

Limit these painkillers. High doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen (Aleve), can cause kidney damage and worsen existing kidney disease. Follow dosing directions carefully.

Get an annual kidney function test. "You should get a blood test and a urine analysis once a year to check kidney function," Dr. Bonventre says. "The urine analysis lets us check for protein in the urine, which would reflect the early stages of kidney disease. And the sooner we catch it, the more likely it is that we can slow the progression of kidney disease and give you a better and longer quality of life."

Image: © Pixologicstudio/Getty Images

About the Author

Heidi Godman, Executive Editor, Harvard Health Letter

About the Reviewer

Anthony L. Komaroff, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Health Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.