Heart Attack Archive

Articles

American Heart Association issues statement on cardiovascular side effects from hormonal therapy for prostate cancer

When giving CPR, stick to standard chest compressions

Research we're watching

If you're a fan of TV medical dramas, perhaps you've seen a doctor try to restart a patient's stopped heart with a single, firm whack to the chest. But this technique, known as a precordial thump, is neither effective nor safe outside the hospital, according to a report in the Feb. 11, 2021 issue of Resuscitation.

Researchers examined data from 23 studies that looked at the effectiveness of the precordial thump and two other uncommon cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) techniques. One, known as percussion pacing, entails less forceful, repeated strikes to the chest. The other, called "cough CPR," is a misnomer because coughing is impossible if you're unconscious. The idea (which is periodically perpetuated on social media) is to cough forcefully and repeatedly during a heart attack to prevent a cardiac arrest.

Cancer survivors: A higher risk of heart problems?

If you're among the nearly 17 million adults in this country who's had cancer, pay extra attention to your heart health.

Thanks to advances in early detection and treatment, people with cancer are living far longer than in past decades. But cancer survivors should be aware that cancer and its treatments can compromise cardiovascular health, according to a recent study from the CDC.

Researchers studied more than 840,000 adults, including about 69,000 cancer survivors, to see how much cancer "ages" the heart. They found that adult men treated for cancer had hearts that appeared to be 8.5 years older than their actual age, while the hearts of women who survived cancer appeared to be 6.5 years older.

Suspected heart attack? Don’t fear the emergency room due to COVID-19

In addition to a prompt assessment and potentially lifesaving treatment, expect a COVID-19 test and extra safety precautions.

Even before the pandemic, people with heart attack symptoms sometimes hesitated to seek emergency care. But during the first wave of COVID-19 infections in early 2020, many more people than usual stayed away. From mid-March to late May 2020, emergency room visits for heart attacks fell by 23% compared with the preceding 10 weeks. And 20% fewer people showed up with strokes, according to the CDC.

Fear of leaving home and risking exposure to the coronavirus likely explains this trend, which has abated over time. "The overall volume at emergency rooms is still somewhat below normal, and we're seeing people who come in many hours or even a day after their heart attack symptoms began," says Dr. Joshua Kosowsky, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Harvard Medical School. These people sometimes have signs of heart damage that might have been easier to reverse or treat if they had come in right away, he adds.

Fight chronic inflammation and cholesterol to protect your heart

It takes a one-two punch to lower these risks for heart disease, heart attack, and stroke.

High cholesterol has long been known as a bad actor in heart health. Too much LDL (bad) cholesterol in your blood can lead to fatty deposits in your arteries and the formation of artery-narrowing plaque (atherosclerosis), heart attacks, and strokes.

But LDL doesn't act alone. Chronic inflammation — a persistent activation of the immune system — also fuels heart attack and stroke risks. That means you must address both high LDL levels and chronic inflammation to protect your health.

Blood thinners after a stent: How long?

After receiving a stent, people normally take aspirin and another anti-clotting drug for up to a year afterward and sometimes longer. Doctors adjust the timeline depending on an individual's situation.

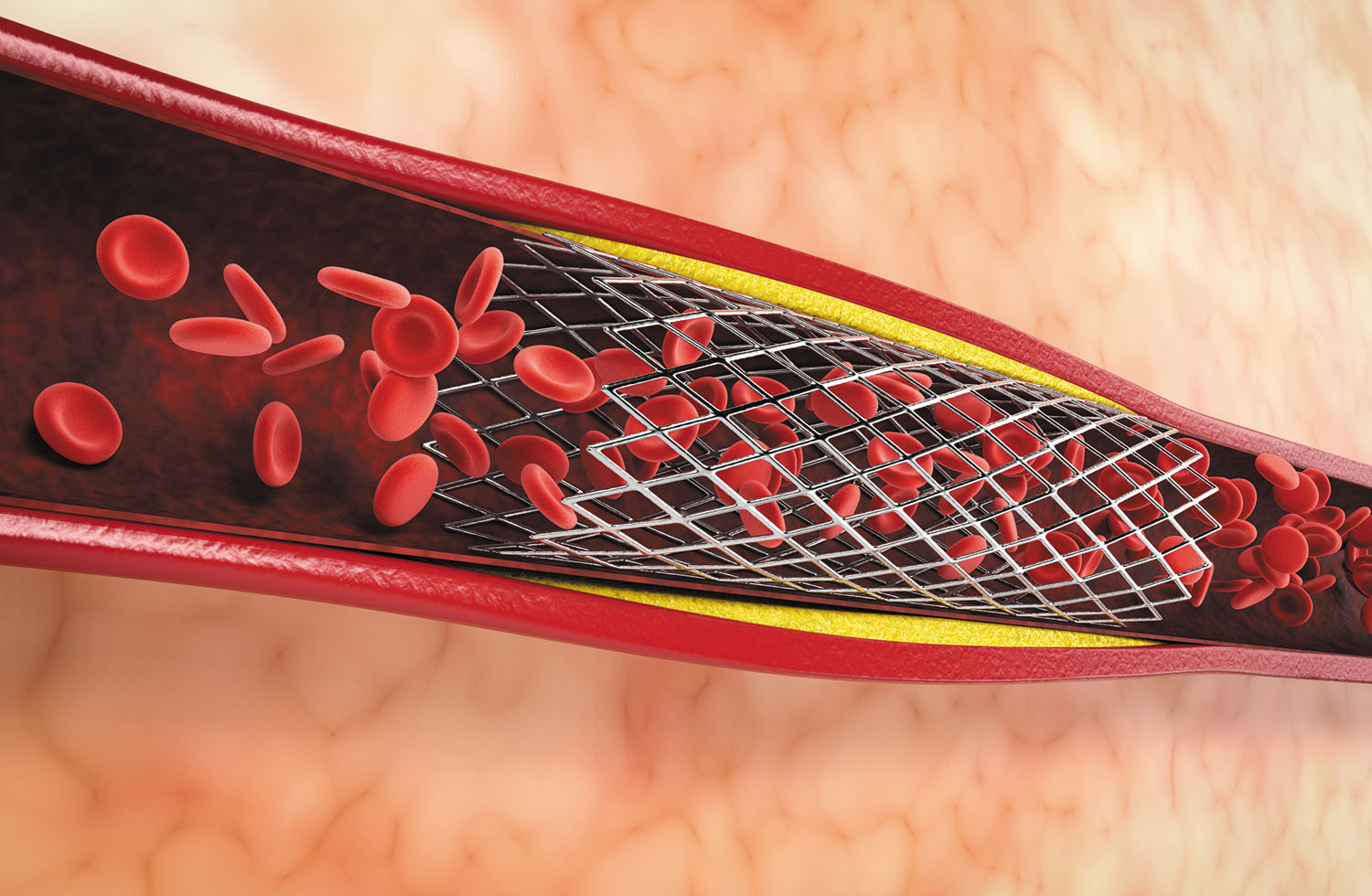

The story on heart stents

Whether you've had a stent placed or may need one in the future, here's what you should know about these tiny devices

Close to a million heart stents to open blocked or narrowing arteries are implanted each year in the United States, and as you age, the odds rise that you'll end up on the list of recipients.

"Getting a stent can save your life during a heart attack, but what you do after the procedure can dictate your future heart health," says Dr. C. Michael Gibson, a cardiologist with Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

How much will fried foods harm your heart?

News briefs

Fried foods carry heart risks in part because they spur inflammation. But how many servings of crispy French fries does it take to raise your risk for cardiovascular disease? Not many, suggests a large analysis published online Jan. 18, 2021, by the journal Heart. Scientists pooled the findings of 17 studies on fried foods and problems like heart attacks, clogged coronary arteries, heart failure, and stroke. The studies included more than half a million people. Researchers also looked at the data from another six studies assessing the association of eating fried food and dying prematurely. Those studies involved more than 750,000 people. People who ate the most fried foods each week were 28% more likely to have heart problems, compared with people who ate the least. Each additional 114-gram (4-ounce) serving of fried foods per week bumped up overall risk by 3%. But the analysis failed to show that people who ate lots of fried foods were more likely to die prematurely. Besides provoking inflammation, fried foods are often also high in sodium as well as harmful saturated fats. If you choose to indulge in them, do it sparingly. And avoid foods fried in animal fats; instead, choose foods fried in vegetable oils.

Image: © Amarita/Getty Images

When it comes to activity, the more the better

In the journals

Regular exercise is good medicine, but more may be better, suggests a study published online Jan. 12, 2021, by PLOS Medicine. Scientists asked more than 90,000 people without heart disease to wear a fitness tracker for a week to measure the duration and intensity of their physical activity. Five years later, they found that the most active people were less likely to have had a heart attack or stroke or be diagnosed with heart disease.

That's no surprise, but the researchers also discovered that risk continued to shrink as weekly minutes of activity and intensity rose. People who exercised the most and at the highest intensity had the best odds of maintaining good cardiovascular health. Guidelines recommend people get 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, but these findings suggest that trying to do a little extra — whether in time, intensity, or both — offers more reward.

Arm yourself to get better blood pressure readings

In the journals

Blood pressure readings are usually done on only one arm, but a new analysis makes the case for checking both arms, as the difference between them may suggest an elevated risk for heart disease. The findings were published in the February 2021 issue of Hypertension.

Researchers examined 24 studies that measured blood pressure in both arms in 53,827 adults without high blood pressure. They found that a difference of more than five points between the left and right arm systolic readings (the top number) was linked with a 9% higher risk for a first-time heart attack or stroke and a 6% increase in cardiovascular death within 10 years. The greater the difference between the two readings, the higher the risk.

Respiratory health harms often follow flooding: Taking these steps can help

Tips to leverage neuroplasticity to maintain cognitive fitness as you age

Can white noise really help you sleep better?

Celiac disease: Exploring four myths

What is prostatitis and how is it treated?

What is Cushing syndrome?

Exercises to relieve joint pain

Think your child has ADHD? What your pediatrician can do

Foam roller: Could you benefit from this massage tool?

Stepping up activity if winter slowed you down

Free Healthbeat Signup

Get the latest in health news delivered to your inbox!

Sign Up