What do the new mammography guidelines mean for you?

Image: Bigstock

Women can devise their own breast cancer screening schedules based on their risk and preferences.

If you tend to "go by the book" for preventive health care, you probably get a flu shot each fall, have a colonoscopy every 10 years, and generally follow the experts' recommendations. But what do you do about mammograms? For decades, the two most influential expert groups—the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—haven't agreed about when to start having mammograms, how often to have them, or how long to keep on having them. Although the two groups come a little closer together with their most recent guidelines, they still disagree about breast cancer screening for women ages 45 through 54.

Dr. Nancy Keating, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School and an internist at Brigham and Women's Hospital, sums up the situation: for women older than 40 who are at average risk, there is no single right answer to the question "Should I have a mammogram?"

Mammography isn't perfect. It is associated with a substantial rate of both "false negatives"—missed cancers—and "false positives"—images that suggest cancer when it isn't present. According to the National Cancer Institute, mammography misses about 20% of cancers. In addition, 100 of every 1,000 women who have mammograms at any screening will be called back for further testing because of a suspicious finding. Yet only five of those 100 will actually have breast cancer.

Moreover, about 19% of cancers detected by mammography will never cause symptoms or become life-threatening. That's because mammograms detect abnormalities like ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)—a buildup of abnormal cells within the breast ducts—which is considered a precancerous condition. DCIS is usually treated with surgery and often radiation as well, even though a majority of DCIS lesions would never progress to outright cancer. Identifying and treating such "harmless" conditions is also known as overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Finally, about 85% of women who die of breast cancer would have died whether or not they had a mammogram. There is growing evidence that some tumors have already shed cells into the blood before they are large enough to be evident on a mammogram.

The new guidelines

In developing their guidelines, both organizations reviewed reams of evidence to weigh the benefits and risks of mammography. Most of the information they considered was from large observational studies in which researchers tracked the health of women who followed different mammography schedules. The ACS published its new guidelines Oct. 21, 2015, in The Journal of the American Medical Association. The USPSTF has a draft of its 2015 guidelines on its website, www.screeningforcancer.org.

The ACS experts determined that the risk of breast cancer is so low in women under 45—only about six in 1,000 women ages 40 to 45 will develop it over the next five years—that the harms of mammography likely outweigh the benefits in this age group. The organization recommends annual screenings beginning at age 45 because the likelihood of getting breast cancer increases at that point.

The ACS recommends annual screening for women ages 45 through 54 because some evidence suggests that annual screening may be associated with finding smaller tumors for women in that group, whereas the same benefit was not found for older women. It recommends biennial screening for older women, who are more likely to develop slower-growing cancers.

The USPSTF determined that women ages 50 through 74 obtain the greatest benefit—defined as reducing their risk of dying of breast cancer—from mammography. It also concluded that screening every two years had benefits similar to annual screening, but caused less harm.

What to consider

Guidelines are only suggestions. If you're trying to decide when—or whether—to have your next mammogram, you may want to talk with your clinician about the following:

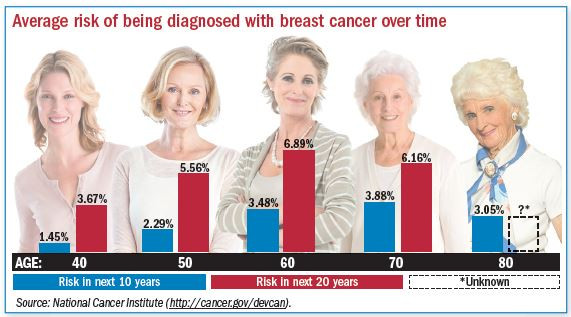

Your personal breast cancer risk. The recommendations are aimed at women who are at average risk for breast cancer (see "Average risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer over time"). That aver-age-risk category omits women who have already had breast cancer, have genetic mutations that in-crease the risk of breast cancer, or had radiation treatments to the chest when they were young, usually for Hodgkin's disease. "Average risk" is based on a broad range of women, so your individual risk may be higher or lower, depending on your family history, lifestyle, weight, or breast-density. Your clinician can use calculators to help you estimate your personal risk.

Mammography's risks and benefits. Your personal breast cancer risk and age are factors in weighing mammography's risks and benefits for you. For example, a woman in her 40s who has a higher-than-average personal risk will have a benefit from mammography similar to that of a woman in her 50s or 60s.

Even though the risk of developing breast cancer is higher in women 55 or older, younger women may have a higher risk for fast-growing, aggressive cancers. That's why they may be more likely to benefit from annual mammograms than older women. However, younger women are also more likely to have false positives and to undergo additional tests, including biopsies.

Your preferences. Your personal beliefs and feelings are as important as the statistics in deciding how often to have mammograms. If you dread the procedures because you find them painful or stressful, you may want to have a mammogram every other year instead of annually. On the other hand, if you couldn't forgive yourself if you were diagnosed with breast cancer after skipping a mammogram, annual screening may be a better option.

Your age. If you're in your 70s or 80s and have several chronic conditions, you may not be willing to undergo treatment for a cancer that's unlikely to kill you. But if you're vigorous and have plans for the next decade, you may want to catch an early cancer.

The bottom line

Current research is directed at finding ways to reduce overdiagnosis by distinguishing precancers and early cancers that are unlikely to advance from those that may spread and become life-threatening. Scientists are also working to develop tests to detect microscopic aggressive cancers before they can be seen on a mammogram. For now, whether or when to have a mammogram is a decision for you to make with your doctor. And while there may not be one "right" answer, you can likely find one that is right for you.

Mammography guidelines for average-risk women based on age |

||

|

Age |

ACS |

USPSTF |

|

40–44 |

No routine screening |

No routine screening |

|

45–50 |

Annual screening |

No routine screening |

|

50–54 |

Annual screening |

Biennial screening |

|

55 or older |

Biennial screening as long as the woman is healthy and has a life expectancy of at least 10 years. |

Biennial screening through age 74. Insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening for women 75 or older. |

|

Sources: American Cancer Society, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. |

||

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.