What to do about dry skin in winter

At this time of year, hands may be red, rough, and raw, and skin may feel itchy and uncomfortable.

Dry skin occurs when skin doesn't retain sufficient moisture — for example, because of frequent bathing, use of harsh soaps, aging, or certain medical conditions. Wintertime poses a special problem because humidity is low both outdoors and indoors, and the water content of the epidermis (the outermost layer of skin) tends to reflect the level of humidity around it. Fortunately, there are many simple and inexpensive things you can do to relieve winter dry skin, also known as winter itch or winter xerosis.

Keeping moisture in the skin

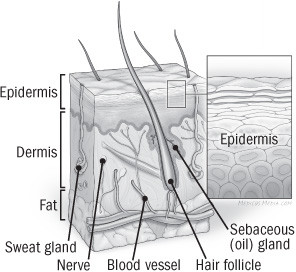

Think of the epidermal skin cells as an arrangement of roof shingles held together by a lipid-rich "glue" that keeps the skin cells flat, smooth, and in place. (See "Anatomy of the skin.") Water loss accelerates when the glue is loosened by sun damage, over-cleansing, scrubbing, or underlying medical conditions — or by winter's low humidity and the drying effects of indoor heat. The result is roughness, flaking, itching, cracking, and sometimes a burning sensation.

Anatomy of the skin

The skin has three layers, each with a distinct role. The lowest or innermost layer consists of subcutaneous fat, which provides insulation, energy storage, and shock absorption. Above that is the dermis, which contains blood vessels, nerves, sweat and oil glands, and hair follicles. The top layer is the epidermis, the skin's main protective barrier and the level where drying occurs. It consists of stacked layers of cells that are constantly in transition, as younger, living cells rise from the lower part of the epidermis and eventually die and fall off after reaching the surface. This continuous cycle completely renews the skin about once a month. |

Skin moisturizers, which rehydrate the epidermis and seal in the moisture, are the first step in combating dry skin. They contain three main types of ingredients. Humectants, which help attract moisture, include ceramides (pronounced ser-A-mids), glycerin, sorbitol, hyaluronic acid, and lecithin. Another set of ingredients — for example, petrolatum (petroleum jelly), silicone, lanolin, and mineral oil — help seal that moisture within the skin. Emollients, such as linoleic, linolenic, and lauric acids, smooth skin by filling in the spaces between skin cells.

In general, the thicker and greasier a moisturizer, the more effective it will be. Some of the most effective (and least expensive) are petroleum jelly and moisturizing oils (such as mineral oil), which prevent water loss without clogging pores. Because they contain no water, they're best used while the skin is still damp from bathing, to seal in the moisture. Other moisturizers contain water as well as oil, in varying proportions. These are less greasy and may be more cosmetically appealing than petroleum jelly or oils.

Skin aging and dryness

Dry skin becomes much more common with age; at least 75% of people over age 64 have dry skin. Often it's the cumulative effect of sun exposure: sun damage results in thinner skin that doesn't retain moisture. The production of natural oils in the skin also slows with age; in women, this may be partly a result of the postmenopausal drop in hormones that stimulate oil and sweat glands. The most vulnerable areas are those that have fewer sebaceous (or oil) glands, such as the arms, legs, hands, and middle of the upper back. Substances in the dermis (below the epidermis) that attract and bind water molecules also decrease with age.

Dry skin is usually not a serious health problem, but it can produce serious complications, such as chronic eczema (red patches) or bleeding from fissures that have become deep enough to disrupt capillaries in the dermis. Another possible complication is secondary bacterial infection (redness, swelling, and pus), which may require antibiotics. (Rarely, dry skin is associated with allergy.) Consult your clinician if you notice any of these symptoms or if measures you take at home provide no relief. For severe dry skin, your clinician may prescribe a cream containing lactic acid, urea, or corticosteroids. She or he may also want to run some tests to rule out medical conditions that can cause dry skin, including hypothyroidism, diabetes, lymphoma, kidney disease, liver disease, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis.

What you can do

Here are some ways to combat dry skin that are effective if practiced consistently:

-

Use a humidifier in the winter. Set it to around 60%, a level that should be sufficient to replenish the top layer of the epidermis.

-

Limit yourself to one 5- to 10-minute bath or shower daily. If you bathe more than that, you may strip away much of the skin's oily layer and cause it to lose moisture.

-

Use lukewarm water rather than hot water, which can wash away natural oils.

-

Minimize your use of soaps; if necessary, choose moisturizing preparations such as Dove, Olay, and Basis, or consider soap-free cleansers like Cetaphil, Oilatum-AD, and Aquanil.

-

Steer clear of deodorant soaps, perfumed soaps, and alcohol products, which can strip away natural oils.

-

Bath oils can be helpful, but use them with caution: they can make the tub slippery.

-

To reduce the risk of trauma to the skin, avoid bath sponges, scrub brushes, and washcloths. If you don't want to give them up altogether, be sure to use a light touch. For the same reason, pat or blot (don't rub) the skin when toweling dry.

-

Apply moisturizer immediately after bathing or after washing your hands. This helps plug the spaces between your skin cells and seal in moisture while your skin is still damp.

-

To reduce the greasy feel of petroleum jelly and thick creams, rub a small amount in your hands, and then rub it over the affected areas until neither your hands nor the affected areas feel greasy.

-

Never, ever scratch. Most of the time, a moisturizer can control the itch. You can also use a cold pack or compress to relieve itchy spots.

-

Use sunscreen in the winter as well as the summer to prevent photoaging.

-

When shaving, use a shaving cream or gel and leave it on your skin for several minutes before starting.

-

Use fragrance-free laundry detergents and avoid fabric softeners.

-

Avoid wearing wool and other fabrics that can irritate the skin.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.