What type of breast screening do you need?

Find out when mammography, ultrasound, and MRI should be used alone or together to detect cancer.

- Reviewed by Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

You've undoubtedly heard the mantra: mammograms save lives. And it's true — screening mammograms lower breast cancer death rates in women 40 and older by 40% when compared with no screening. The imaging test is still considered the gold standard to find breast cancer early, when it's most treatable.

But that's only part of the picture. Even if you diligently schedule an annual mammogram, you might also need other types of imaging, depending on your individual risk factors.

"Women aren't always aware of this unless a physician has actually spoken to them about it," says Dr. Vandana Dialani, chief of breast imaging and co-director of the Breast Care Center at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. "It's important they know who should be getting additional tests."

Mammograms may offer clues to heart disease risk

Mammograms help detect breast cancer, but could they also be tapped to find markers of heart disease? A new study, published online March 15, 2022, by Circulation, suggests the potential for this double-duty scenario in postmenopausal women, though a Harvard expert urges caution in interpreting the findings. The study authors used electronic medical records to track the health of more than 5,000 women ages 60 to 79 after they had mammograms. Study participants had no known history of cardiovascular disease or breast cancer. Those whose images showed breast arterial calcification (a buildup of calcium inside artery walls) were 51% more likely to have a heart attack or stroke during a follow-up period of about six-and-a-half years, and 23% more likely to develop any type of heart disease, than women without this mammogram finding. Breast arterial calcification shows up on mammograms as white areas in the breast's arteries. It is linked to aging, high blood pressure, and diabetes, but it isn't believed to be associated with cancer. Mammograms have long been able to detect calcifications in breast arteries, which are common in women over 60, says Dr. Vandana Dialani, chief of breast imaging and co-director of the Breast Care Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. But radiologists are not required to mention this so-called incidental finding. "This information will be helpful if we have more data to suggest that breast arterial calcifications are an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease," Dr. Dialani says. More research is needed to determine whether these findings should be systematically reported on mammograms. Image: © LeslieLauren/Getty Images |

Who's at higher risk?

The average woman in the United States stands a one-in-eight chance of developing breast cancer in her lifetime, according to the American Cancer Society. But some face higher odds of the disease, which claims more than 43,000 lives in the United States every year.

Who's at greater risk? Chief among us are the nearly 50% of women over 40 whose mammograms indicate dense breasts. This means your breasts have a relatively high proportion of glandular and connective tissue compared with fat. Women with dense breasts are up to twice as likely to develop breast cancer as are those whose breast tissue is more on the fatty side, according to the National Cancer Institute.

As mandated in many U.S. states, women whose breasts are deemed dense should receive a letter after their mammogram recommending additional screening — typically with either ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). "Ideally, that's when you should be having a conversation with your physician about what supplemental tests should be done," Dr. Dialani says.

In addition to dense breasts, certain women are prime candidates for extra screening because they have other breast cancer risk factors, such as

- a mother or sister who developed breast cancer before menopause

- a genetic mutation known to increase breast cancer risk (such as in the BRCA gene)

- significant radiation to the chest before age 30

- past breast cancer.

Your doctor should devise a personal breast cancer screening strategy for you that takes all of this information in-to account, Dr. Dialani says.

Callbacks common with 3D mammograms

The latest version of mammogram technology creates a three-dimensional picture of the breast, viewing it in "slices." But half of all women who get these "3D" mammograms will have at least one false positive — that is, their breasts will be flagged as abnormal but ultimately prove to be cancer-free — over a decade of yearly screenings, new research suggests. The study, published online March 25, 2022, by JAMA Network Open, analyzed data on three million screening mammograms performed on 900,000 women ages 40 to 79. False positives prompt callbacks for additional testing and may lead to unnecessary procedures and needless worry. But even this seemingly high false-positive rate for 3D mammograms is lower than the false-positive rates for two-dimensional mammogram techniques, says Dr. Vandana Dialani, chief of breast imaging at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Dr. Dialani urges women to keep perspective on mammogram callbacks, comparing the process to waiting for additional results from other routine tests, such as blood cholesterol levels. "People always talk about how anxiety-provoking it is to get a callback," she says. "But it's about being cautious with your health." Image: © Paul Biris/Getty Images |

When mammograms aren't enough

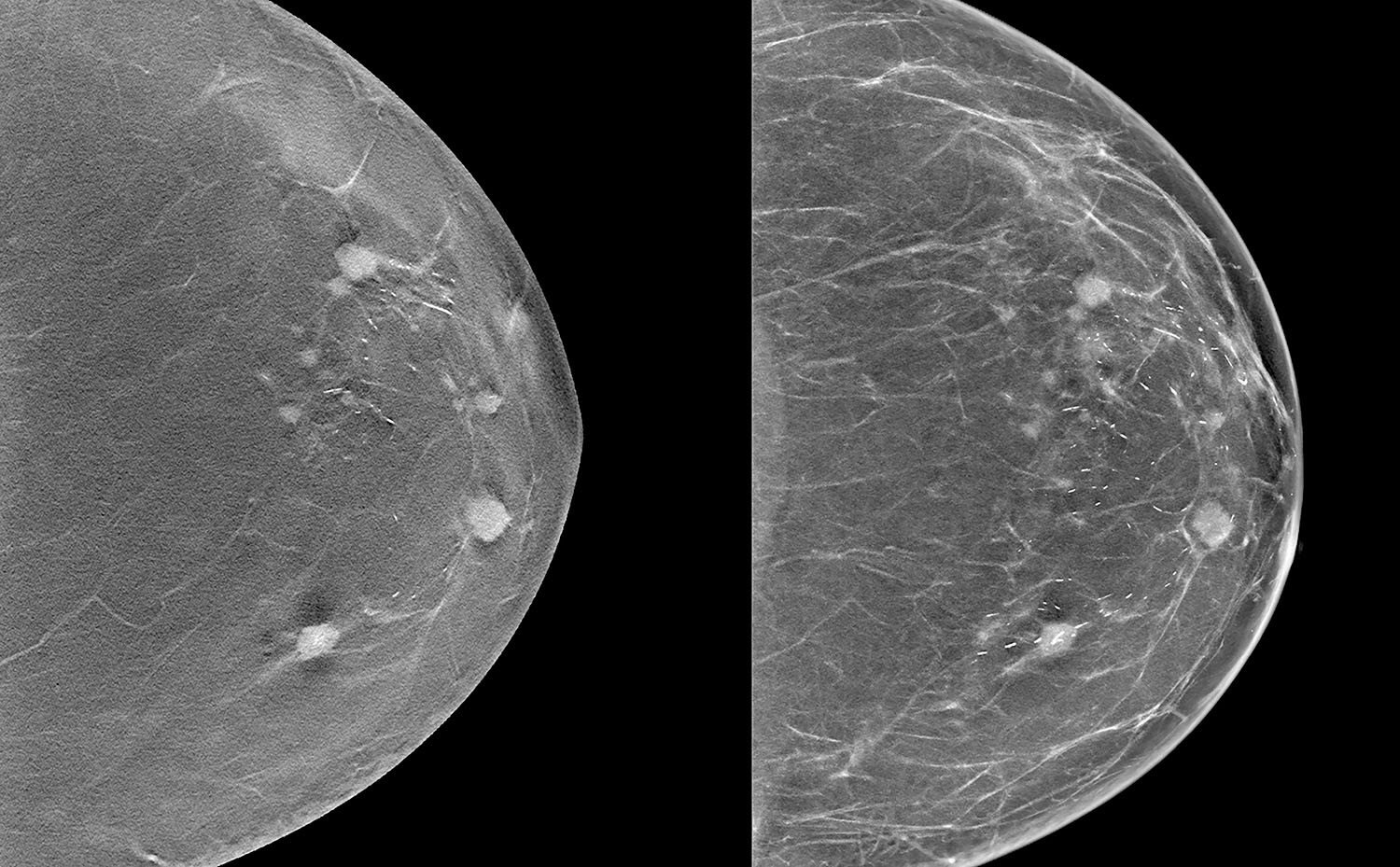

Digital mammography captures views of the breast from several angles using low-dose x-rays. In the resulting images, areas appearing white represent glandular tissue, and black areas depict fat. Although mammograms are highly effective at detecting breast cancer, the images can be harder to read accurately in women with dense breasts because cancer shows up as white areas, just like dense breast tissue.

"What we're trying to see is a white tumor hiding in white glandular tissue," Dr. Dialani explains. "The more dense tissue we see, the less chance we'll be able to see a tumor hiding in that."

But other imaging tests can help detect cancers that might escape notice using mammography alone.

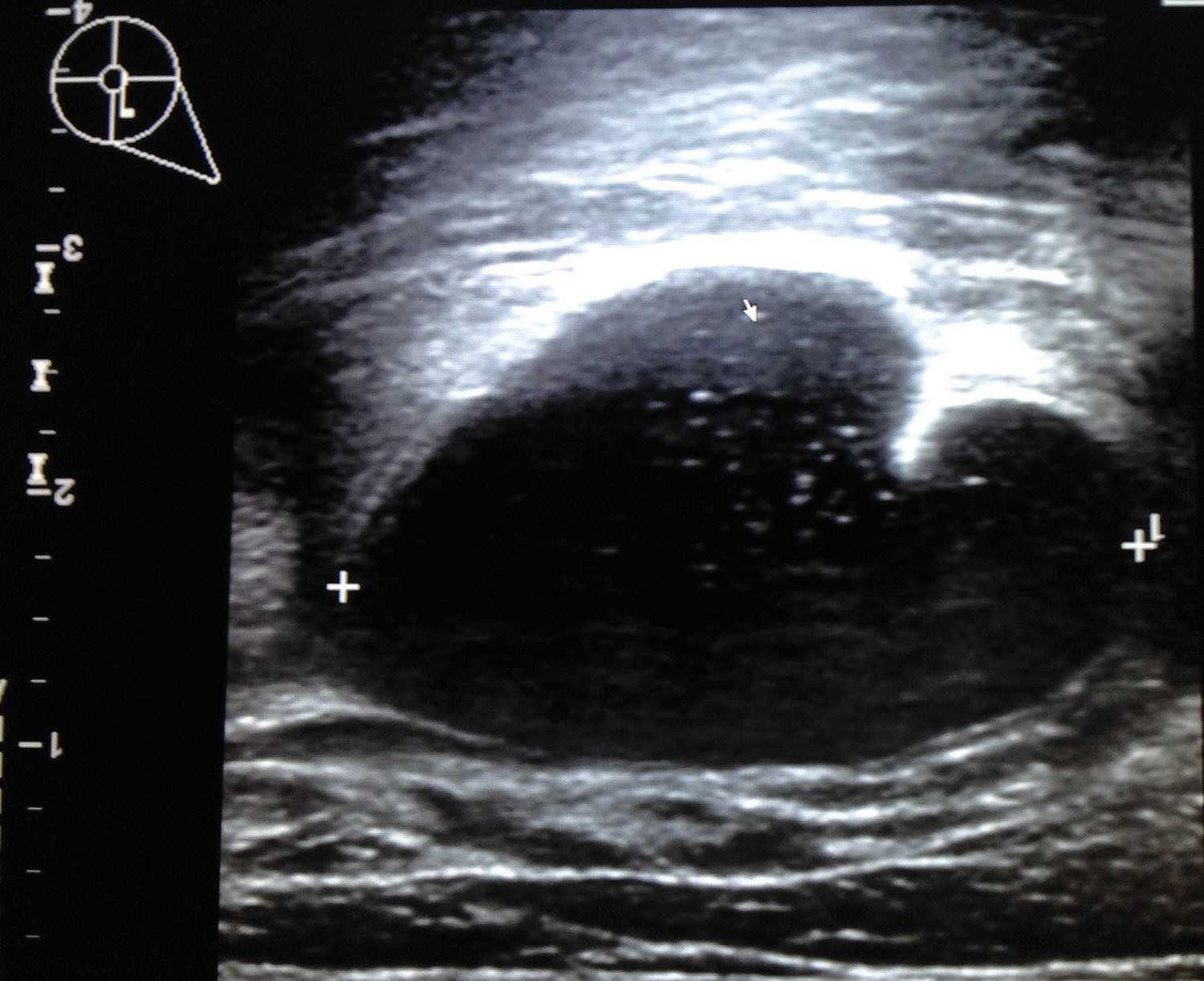

Ultrasound. Using high-frequency sound waves to create images of breast tissue, ultrasound can serve as a supplemental screening method in women with dense breasts. That's because breast tumors stand out by showing up as black on ultrasound — not white, as on mammograms.

When added to mammography, ultrasound can detect two to four more breast cancers per 1,000 women screened compared with mammography alone, Dr. Dialani says.

But ultrasound is almost never a stand-alone screening test to detect breast cancer because it comes with a high false-positive rate. It is best used only when a mammogram is done first. "Used with mammography or even with MRI, targeted ultrasound is more useful in women who've been called back because of a suspicious finding on a mammogram," she says. "It's easy on the patient and not an expensive test. It's a fabulous tool."

MRI. Blending radio waves and a powerful magnet with contrast fluid injected into the patient to "light up" cancers, MRI creates highly detailed pictures of the breast. MRI finds 18 to 20 breast cancers per 1,000 women screened, six times more than mammography alone and about four times more than a combination of mammography and ultrasound, Dr. Dialani says.

But while it's considered the best test to detect breast cancer, MRI isn't currently used for screening in everyone, mainly because it's extremely expensive and not widely available. Instead, it's performed at staggered six-month intervals alternating with mammography only in people considered at high risk of breast cancer.

Health insurance typically covers breast MRI screening for those whose lifetime risk of breast cancer is gauged to exceed 20%. Ask your doctor to calculate your risk of breast cancer, Dr. Dialani says. If your lifetime risk is higher than 20%, consider supplemental breast screening, especially breast MRI.

Image: © Carol Yepes/Getty Images

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.