Nine for 2009: Nine ways to healthier eating, Mediterranean style

There are good reasons to follow the traditional diets of Greece and Italy.

If you're thinking about New Year's resolutions, consider making 2009 the year you try eating the Mediterranean way. Picture a plate full of fresh vegetables, tasty grains, and fish or beans prepared with olive oil and sprinklings of herbs, spices, cheeses, and nuts, accompanied by a glass of red wine and some hearty bread. These are key components of the traditional, largely plant-based diet of countries surrounding the Mediterranean. It's not only delicious but also appears to protect against heart disease and many other chronic conditions.

A Mediterranean-style diet isn't the only traditional eating pattern that's good for your health. But it's been studied the longest, and it's practical for most Americans. It also fits in nicely with the latest approach to nutrition. Experts stress overall eating patterns rather than "magic bullets" that don't always live up to their advertising (for example, vitamin E, beta carotene, and isoflavones). Individual nutrients are important — for one thing, they can help to correct deficiencies — but the greatest health benefits are likely to result from the synergy of many foods with different nutrient qualities.

History of the "Mediterranean diet"

The Mediterranean region is culturally diverse, and its inhabitants don't all eat the same way. But a typical Mediterranean dietary pattern was identified in the late 1950s as part of the landmark Seven Countries Study, led by Ancel Keys of the University of Minnesota. Keys spent more than a decade studying lifestyle, particularly the influence of diet, and its relationship to cardiovascular disease in nearly 13,000 men in Finland, southern Italy, the Greek islands of Corfu and Crete, Japan, Yugoslavia, the Netherlands, and the United States. Keys was particularly interested in dietary fat and was one of the first to recognize that there are "good" fats and "bad" fats, noting that despite limited medical care and sometimes high fat consumption (in Crete, for example, up to 40% of calories came from fat), the Greek and Italian participants lived the longest and had the lowest rates of heart disease (so did the Japanese, whose diets contained very little fat). The fats consumed in Greece and Italy were generally unsaturated, deriving mainly from olive oil and fish. The highest rates of heart disease were found in countries where people consumed the most saturated fat (for example, Finland and the United States).

The Seven Countries Study introduced the Mediterranean style of eating, which was modeled on the typical dietary pattern of Crete in the 1950s and 1960s, to a wider audience. But the term "Mediterranean diet" was more or less formally adopted in 1993 at a meeting organized by the Harvard School of Public Health and the Oldways Preservation and Exchange Trust, a nonprofit group that promotes education on healthful eating and the diets of traditional cultures. The Harvard nutrition experts described a traditional diet consisting mostly of plant foods (fruits, vegetables, grains, beans, nuts, and seeds), with animal protein consumed chiefly in the forms of fish and poultry, olive oil as the principal fat, and wine taken with meals. They also noted that this diet was complemented by regular physical activity in the form of "work in the field or kitchen."

|

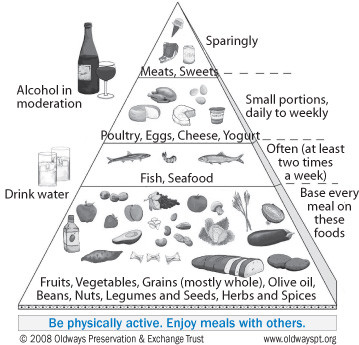

Mediterranean Diet Pyramid

The Mediterranean Diet Pyramid represents the traditional dietary patterns of Greece and Italy that have been associated with lower rates of chronic disease and greater longevity. It's designed to give a sense of the relative proportions of various foods in an overall diet and how frequently they're eaten. The emphasis is on planning every meal around plant foods (the large, lower portion of the pyramid). |

Evidence piles up

Features of the traditional Mediterranean lifestyle other than diet undoubtedly contribute to the region's health. But there are indications that the dietary pattern alone offers important protections. There have been many positive findings over the years. Here are some of the latest:

-

A two-year randomized trial comparing low-fat, low-carb, and Mediterranean diets in middle-aged, mildly obese men and women found that the low-carb and Mediterranean diets resulted in greater weight loss than the low-fat diet. The Mediterranean diet also lowered LDL (bad) cholesterol most and controlled blood sugar most effectively (The New England Journal of Medicine, July 17, 2008). Only 15% of study participants were women, but in that group, those who followed the Mediterranean diet lost, on average, about 13 pounds more than the women on the low-fat diet and 8 pounds more than the women on the low-carb diet.

-

Women in the Nurses' Health Study whose diet most closely approximated the Mediterranean pattern were 28% less likely to die of heart disease or stroke during an 18-year period than women who ate a "Western" diet (Circulation, July 15, 2008).

-

In a 13,380-person Spanish study, participants most closely following a traditional Mediterranean diet were a whopping 83% less likely to develop type 2 diabetes than those following the diet least closely (BMJ, June 14, 2008).

-

An analysis of 12 studies that followed more than 1.5 million adults in the United States, northern Europe, Greece, Spain, and Australia for periods ranging from three to 18 years found that people who strictly followed the Mediterranean diet were 6% less likely to die from cancer, 9% less likely to die from cardiovascular disease, and 13% less likely to develop Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer's disease (BMJ, online, Sept. 12, 2008).

-

A study of cognitive function in 2,258 older Americans over a four-year period found a 40% reduced risk for Alzheimer's disease among those who most closely followed the Mediterranean diet (Annals of Neurology, June 2006).

-

The National Institutes of Health (NIH)–AARP Diet and Health study, involving nearly 400,000 women and men, ages 50 through 71, is the largest U.S. investigation of the Mediterranean diet and mortality. It found that people who most closely followed this diet were about 20% less likely to have died of heart disease, cancer, or any cause over a five-year follow-up period (Archives of Internal Medicine, Dec. 10/24, 2007).

Research has also found Mediterranean-style eating associated with improvements in rheumatoid arthritis, reduced risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and reduced risk for recurrence of colon cancer.

|

Rebalance your plate When you plan a meal, mentally divide the plate down the middle. Fill one-half with vegetables, one-quarter with whole grains or healthy starch, and one-quarter with protein-rich foods low in saturated fat, such as fish, poultry, or beans. |

Why it may work

We don't know all the mechanisms behind the healthfulness of the Mediterranean diet. But research suggests a number of factors. For one thing, the monounsaturated fats in olive oil and fish can have anti-inflammatory effects, which may help stave off heart disease and many other conditions. By slowing digestion, the fiber in whole grains and legumes can help keep blood sugar under control; fiber also creates a feeling of fullness, which may help quell appetite — a boon to avoiding becoming overweight. Other compounds in plant foods appear to act on the cellular level, affecting the aging process, cancer development, and the body's response to treatments such as chemotherapy. And of course, Mediterranean-style eating excludes many foods known to cause health problems: saturated fat from animal sources, trans fat, and refined carbohydrates.

|

Is there a clinician in the kitchen? Harvard experts think that sending primary care clinicians to cooking school can help improve America's eating habits. Find out why and how at /womenextra. |

Getting started

With any eating plan, the key to success is sticking to it. Here, the Mediterranean diet has a number of advantages. The ingredients are readily available and can be easily and simply prepared; the foods are varied and taste good; and meals aren't likely to leave you feeling hungry or deprived. Here are some suggestions for getting started.

1. Pile on the vegetables. Nearly all vegetables are nutrient-rich, low in fat and calories, high in fiber, and loaded with health-promoting compounds. The key is variety, so eat many different — and different-colored — ones (especially bright yellow, orange, deep green, and red). There are plenty to choose from, so you don't have to force yourself to eat things you don't like. Keep it interesting: Explore local farmer's markets, the produce aisle of your grocery store, and opportunities for community farming. Vary your cooking method: instead of steaming or boiling vegetables, try grilling or roasting them. Make your salad a main course by adding nuts, diced chicken or fish, and grated cheese. Pressed for time? Buy pre-packaged salads and pre-cut fresh vegetables. Keep plenty of frozen vegetables on hand to heat and serve topped with olive oil and herbs or nuts, add to stir-fries, or incorporate in whole-grain pasta dishes or rice salads.

2. Eat lots of whole fruit. Like vegetables, fruits are generally low in calories and full of nutrients, antioxidants, and fiber. (You lose out on the fiber, however, when you choose fruit juice instead of whole fruit.) Most fruits are naturally sweet; they make great snacks and desserts. Again, variety is the key. Keep it interesting: Add pear or apple slices to garden salads. For breakfast, have whole-grain cereals with yogurt and berries — or top toasted whole-grain bread with peanut butter and sliced banana. For dessert, serve fruit layered with yogurt, drizzled with honey, and sprinkled with chopped nuts. Broil or grill fruit slices brushed with oil, and then sprinkle them with cinnamon. To enjoy a variety of fruits year-round, buy bags of frozen out-of-season and exotic fruits (mango, papaya, passion fruit). Whirl frozen fruit into a smoothie made with low-fat yogurt and half a banana.

3. Go a little nuts. Nuts contain many antioxidants and other nutrients. Walnuts, in particular, are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, which reduce cardiovascular risk and have anti-aging effects in the brain and skin. Unlike snacks made from refined grains or sugar, nuts have a low glycemic index, which has a steadying effect on blood sugar, and they're good at satisfying hunger. But they're calorie-dense, so restrict yourself to small amounts — no more than a small handful (160 to 180 calories) a day. Keep it interesting: Sprinkle chopped pecans or walnuts on salads, fruit, or yogurt. Top cooked vegetables with sliced almonds. Dip olive oil–coated fish or poultry in ground nuts before baking or roasting. Brush small slices of whole-grain bread with olive oil, and then sprinkle them with — or dip them in — a mixture of ground nuts, seeds, and spices.

4. Go for the grain, the whole grain. Grains are mostly carbohydrate, and we need carbohydrates for energy. But highly processed grains like white pasta, white rice, white bread, and refined-grain cereals and snacks are stripped of important nutrients, including their fibrous coating. With little or no fiber to slow their digestion, refined grains can cause blood sugar levels to spike. Eventually this can lead to weight gain, diabetes, heart disease, and other disorders. Whole grains contain more vitamins, minerals, and protein, and they have a stabilizing influence on blood sugar levels. Keep it interesting: Maybe you're already eating whole-wheat bread, brown rice, and oatmeal, but there are many more tasty options to explore. Try pasta made with whole-grain flour or a mixture of whole-grain and legume flours (with at least 4 to 6 grams of fiber per 2-ounce serving). Instead of regular oatmeal (from rolled oats), try the steel-cut variety: it's chewier and slightly nuttier in flavor. Other interesting possibilities: whole-grain cornmeal (not the degerminated kind); the South American grains amaranth and quinoa; farro, a wheat grown in ancient Egypt and now part of the Italian diet (in the form of semolina); barley, which (like oats) has a type of fiber that helps lower cholesterol; spelt; kamut; kasha; sorghum; buckwheat; and wild rice. Several of these grains can be cooked like hot cereal or rice. Some are ground into flour and can be incorporated in breads, muffins, and pizza dough. Amaranth, buckwheat, quinoa, sorghum, and wild rice are gluten-free. For more information about whole grains, visit the Whole Grains Council on the Web at www.wholegrainscouncil.org.

5. Eat good fats. Thirty to forty percent of calories in the traditional Mediterranean diet come from fat, half or more of it from olive oil. This healthy monounsaturated fat lowers both total and LDL cholesterol when it's used to replace unhealthy saturated fats — like the fats in whole milk, butter, and meat — and trans fats (especially the solid vegetable fat used to fry foods and in commercial baked goods). Canola oil and nuts are also rich in monounsaturated fat. Another source of good fat is fish rich in heart-healthy omega-3 fatty acids — for example, anchovies, sardines, mackerel and salmon. Keep it interesting: Use high-quality olive oil in salad dressings, on vegetables, and instead of butter on bread. Brush olive or canola oil on vegetables, fish, and poultry before broiling, roasting, or grilling. To cut back on saturated fat, use fish instead of meat in some recipes. Add small amounts of cooked fish to salads, pastas, and soups.

6. Spice it up. Mediterranean cuisines benefit from a climate ideal for growing spices and herbs, which impart flavor, add nutrients, and can substitute for salt. Some also have medicinal uses; for example, mint aids digestion. So spice up your meals, especially if it encourages you to enjoy a greater variety of good foods. Keep it interesting: When fresh herbs are available, use them instead of dried herbs in salads and grain or other dishes. Try growing your own herbs. Visit ethnic markets to explore the spices and herbs of other cultures; ask at the market how they're used, or look them up on the Internet or in cookbooks.

7. Love those legumes. Mediterranean cuisine relies on legumes — plants that house their seeds in pods, like peas, lentils, and beans. Legumes are an excellent low-fat source of protein, vitamins, minerals, and fiber, and are a good substitute for meat. If you don't have time for rehydrating dried beans, use canned or frozen. Keep it interesting: Add legumes to soups and salads. Use beans instead of meat in stews or casseroles. Puree beans with herbs, spices, some stock, and a splash of olive oil and serve as a sauce over whole-grain pasta. Substitute lentils or beans for pasta or potatoes at meals.

8. Toast your good health. Wine (particularly red wine) with meals is a feature of the Mediterranean diet, but any alcohol should be taken in moderate amounts and considered optional. If you're pregnant or at risk for alcohol problems, you should avoid drinking altogether. Moderate drinking (one glass a day for women) has been associated with reduced risk for heart disease and death from all causes. Alcohol of any kind increases HDL (good) cholesterol, improves insulin sensitivity, and reduces inflammation. Wine in particular contains small amounts of plant substances called flavonoids that have demonstrated anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity in laboratory experiments.

9. Slow down. Ancel Keys' research convinced him that diet played a primary role in the health benefits he observed in the Mediterranean, but later, he concluded that the leisurely pace of life also mattered. These days, that may seem moot if you're juggling work, family, and other responsibilities. But eating on the run and under stress can cause heartburn and less efficient absorption of nutrients. Eating fast also makes it more difficult to achieve and maintain a healthy weight. In a study at the University of Rhode Island, researchers fed two groups of women the same pasta and vegetable dish. They asked one group to eat as quickly as possible and the other to chew slowly, savor the food, and lay the fork down between bites. The fast eaters finished in 10 minutes; the slow eaters, who took three times as long, consumed 70 fewer calories but enjoyed the meal more and felt fuller afterward. That's one more reason to embrace the traditions of the Mediterranean, where eating well includes taking time to enjoy the meal.

|

For more information For links, recipes, and ideas on buying, preparing, and serving healthy foods, visit /womenextra. |

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.